How fortuitous that Native American Heritage Month comes at a time when I’ve been invited to write a book chapter about my work in Native Science.

How fortuitous that Native American Heritage Month comes at a time when I’ve been invited to write a book chapter about my work in Native Science.

Below I’ve woven together words that describe what I do for the book’s editors and I welcome your advice about whether the description makes sense to you:

My work examines the ruptures and linkages between indigenous sciences and mainstream sciences, and I study how public discourse of environmental, science, health and risk issues impact American Indian tribes.

I’ve written about the launching of a copper mine on seded land in Wisconsin, conflicts over the provenance of Kennewick Man (The Ancient One), and management of salmon fisheries at the Columbia River framed in public channels of discourse, particularly in mass media.

Public discourse tends to frame such environmental conflicts narrowly, often in Western scientific terms and along political dimensions that ignore or misrepresent indigenous perspectives and epistemologies.

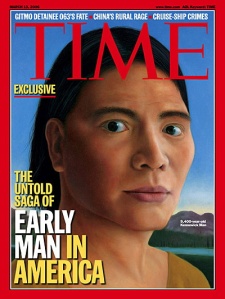

An example of this narrow discourse emerges from a news feature about Kennewick Man—the 9200-year-old skeleton uncovered in the Columbia River in North America—where the reporter claims the “central question of concern is who was here first?”

I argue this question is one posed by anthropologists, politicians, news reporters and others with an interest in studying the skeleton—not indigenous peoples.

Local tribes attempted (unsuccessfully) to have the skeleton returned under the United States’ Native American Graves and Repatriation Act–legislation designed to honor tribal sovereignty and return artifacts to tribes.

While it is true that Kennewick Man’s genetic haplogroup is of great interest to many scientists, the more salient issue to tribes is who gets to determine the “central question of concern.”

My research has explored the ways in which truth-claims surrounding environmental justice issues that affect North American tribes have rested principally within the province of non-Indians.

Thanks for listening. I welcome your thoughts.

7 November Blog for National Native American Heritage Month

Time magazine cover story on Kennewick Man from http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=kennewick+man&qpvt=kennewick+man&FORM=IGRE#view=detail&id=8E6E8F71E130838665574936C8934CAA8740ABB7&selectedIndex=48

Hi Cynthia,

Thank you for your ongoing courage.

I believe I understand your introduction; you have written well. I do not know whether those who are not versed in the conflicts will understand, not do I know whether anything you can do will improve that. I imagine what is required is for others to realize the problematic nature of the terms of the discussion.

Warmly,

Michael

LikeLike

Insightful comments: I will take these to heart and be more specific. Just what I need. THank you for your confidence

LikeLike

You write with courage and patience. The inormation and perspective I read when I receive you blogs are both very interesting and some times discourageing. That we must do battle every day for basic human rights in a country that proffesses human rights is very dicouraging.

LikeLike

I appreciate your kind words; thank you

LikeLike

I can’t agree more that western thinking and notions of ‘science’ dominate the media voice in America. I also hear a challenge of cross cultural communication. Who are the cultural interpreters willing to publish Native American perspectives in mainstream media? How do the tribes find a mainstream voice when they value silence, autonomy and man’s relationship with the land?

LikeLike

A viable culture is one that grows and changes. And as it grows and changes, the people of that culture develop different opinions. So, how DO the tribes find a unified voice when they have been shattered and scattered? Or shall we, in condescending patriarchal fashion, decide what will be the best for the poor native peoples? Which native peoples are we talking about, anyhow? The managers of the Grande Rhonde Casino? The single mother on the Warms Springs reservation who is living on welfare? The Navaho lawyer in a four bedroom home in Albuquerque New Mexico? Everyone has their own agenda and perspective. What is best for one is not necessarily best for all. Who decides and how should they decide?

LikeLike