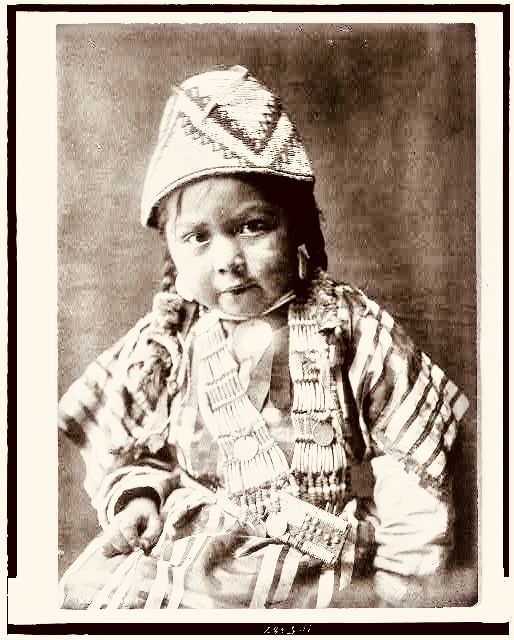

[The Wasco and Wishram lived along what is now called Hood River in Oregon, and lost their territory to settlers in the 1800s. Edward S. Curtis captured an image of a Wishram girl in 1909. Photo from the Library of Congress, in the Public Domain.]

A Postcard Tradition

Picture postcards in the US have long presented an affordable way to share beach vacations with relatives, and offer a quick channel to keep in touch.

My introduction to writing-in-brief came in the 1960s from my mum, who sent postcards from around the world (literally) to her relatives and friends.

She would find a rack of cards in a candy store or tobacconist’s—at the Souk in Esfahan, Iran, or at Olivera Street in Los Angeles (she pronounced the city like the 90-degree line-drawing in your Trigonometry text—”Las ANGLE-less”) and buy two handfuls of picture postcards.

Mum would find a place where she could light up a menthol cigarette, drink a gin-and-tonic, and send off a missive about her latest excursion to a pal stateside.

When her mother died, we discovered my Eeko (grandmother) kept a scrapbook of all the postcards mum sent, which covered regions ranging from the Soviet Union to our Native reservation in Oklahoma.

I fully embraced my mother’s custom of writing postcards, which—for many years—I could find at most community pharmacies or five-and-dime stores when I returned to the States for college.

When visiting a Native history exhibit in Chicago, I searched for postcards that reflected the display, or ones that explored the area’s rich history of Indigenous peoples prior to settlement, so I could share the exhibit with others.

The Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Miami, HoChunk, Wyandot, Chippewa and many more communities and tribes call the region home.

While I could find cards of the jagged Chicago skyline, the gothic Tribune skyscraper and the beloved Cubs baseball team, the closest I got to Native Americans was a postcard of the men’s hockey team named for the Sauk warrior Black Hawk.

There seems no market in the postcard business for Illinois’ Indigenous history, and on visits of late to Albany (New York), Washington DC and the Oregon coast—and even in Portland where I live—I find no postcards acknowledging aboriginal peoples.

I began making my own.

Hand-made Cards

In my earliest attempts I glued my own photographs to card stock for a homemade communique.

To share some aspects of Indigenous life in Oregon, I chose images of plants (such as skunk cabbage—Symplocarpus foetidus—used for Indigenous medicine) and drew pictures of cicadas (once consumed by tribal communities in the Midwest) when they emerged from underground hibernation.

I graduated from glue to the printed press, and created cards with snaps I took of Wounded Knee (South Dakota), Wy’East (Mount Hood) and Loowit (Mount St. Helens).

With each card, I included a few sentences about Native history of the region.

The more I travelled, the more I looked for traces (and especially acknowledgements) of Indigenous lives, and not just in museums—street names, plaques, statues—any mention of Native peoples.

Now I prepare in advance for travel, meaning, I read about local, Indigenous history before I make a trek.

Sometimes in my research I find images of local denizens, such as the Wishram girl pictured above.

Her image graces the front of a card I made when I travelled to Hood River, which compelled me to learn about the communities where lives were ravaged by settlers claiming the lands as their own and by dams at the Columbia that forever changed the ecological relationship between the original peoples and river life.

Recently I’ve been researching denizens who lived near Clatskanie, Oregon—an area named for the Tlatskanhi people—and current home to the Buddhist community at Great Vow Monastery, where I am a lay member.

In addition to the Tlatskanhi and Chinook, the region was peopled by the Clatsop on the Oregon coast (where Lewis and Clark ended their westward journey before returning homeward) and the Cowlitz tribe to the east, near Longview (Washington).

Scholars conclude that as many as 90 percent of the Native peoples on the coast and near the Clatskanie River perished after the arrival of settlers, most likely because of diseases, such as smallpox, measles, typhoid, pertussis and malaria.

Dr. David G. Lewis (Grand Ronde) notes in his 2023 book, Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley, the Tlatskanhi and Chinook were removed to a temporary reservation in 1855 and, again, in 1856—to the Grand Ronde reservation—although few remained to face the 100-mile journey.

One scholar, John R. Swanton, noted in a 1953 report that only eight individuals survived by the time of their move to Grand Ronde, according to ethnologist James Mooney’s 1928 account..

Swanton says Mooney estimated 1600 Tlatskanhi were alive in 1780, and that most had perished by the mid-1800s.

My search for images of the Tlatskanhi people has been fruitless, so when I designed a card to pass along a bit of local history, I snapped a picture of a mural in downtown Clatskanie of Chinook salmon, swimming upstream.

The salmon mural, titled, “Homeward Bound,” was completed in 2020 by Mark Kenny, and funded by the regional arts council.

The picture reminds me how Native people’s lives here are tethered to the fish and their life cycles.

And tomorrow I will begin my morning as usual—sitting on the porch with a cup of hot tea, my dog at my feet and my human companion by my side—and I will welcome the summer’s warmth while I breathe the air.

And then I will write a batch of postcards that share a story about the Clatskanie people, who inhabited this part of the world for some 10,000 years.

And I will ask my readers not to forget them.

[Chinook salmon welcome visitors on Nehalem Street in downtown Clatskanie. The mural by Mark Kenny, titled Homeward Bound, was completed in 2020. Photo by C. Coleman Emery.]

Thanks for listening, and please excuse the advertisements. I am looking into how to avoid them while keeping the blog affordable.

Cynthia Coleman Emery

7 August 2024

#nativescience

#greatvow

#clatskanie

#oregonnatives

#landacknowledgements

#nativeamericans

#wishram

#nehalem

#chinook

#hoodriver

#columbiariver

#wishram

#nehalem

#chinook

#hoodriver

#columbiariver

#indigenouswaysofknowing

#nativepress

#nativewaysofknowing

#nativewriter

#osage

I loved reading this informative blog post, Cindy. Thank you! The mural image is stunning. Now I know more about your love of correspondence!

LikeLike

THANKS, Lyndi. True story, of course! And I do love sending them–a little touch to let you know I am thinking of you

LikeLiked by 1 person