8 September 2024

My friend Jan Haaken—a professor of psychology and a filmmaker—is steeped in a fund-raising campaign to clear $25,000 and finish a documentary about how faculty, students, staff and college communities in the US cope with speech freedoms, academic integrity, and protests surrounding current skirmishes in Israel and Palestinian territory.

Dr. Haaken says the question she gets asked most often isn’t what (what is the film about?) but, rather, when: when can we see the documentary?

While she, her co-director Jennifer Ruth, and her nine-member team are editing the final film, a website teases viewers with a trailer, details of the documentary, bios of featured commentators, resources for educators, questions for the team, and, naturally, a link to donate to the production.

Once completed, the film will make its rounds at venues across North America and beyond.

With nine feature films and five short films under her belt, Dr. Haaken’s latest inquiry examines how media coverage, internal campus responses and communication across college campuses have been framed following Hamas‘ 7 October 2023 attack on the Israeli side of the border with Gaza.

Gaza—a strip of land once controlled by Egypt—is now claimed by Palestinian refugees and is considered the most densely populated territory on earth: just 141 square miles altogether: the size of the city of Philadelphia but with a population of Philadelphia and Portland (Oregon) combined.

Thousands Die, Thousands Left Homeless

Turns out protests, vigils and public gatherings began worldwide hours after the attack by Hamas—a group the US considers a terrorist organization.

Some 1,195 people were killed in Israel on 7 October, according to Agence France-Presse: about 69 percent were civilians.

Israel responded swiftly and blocked access to “food, water and medical supplies,” notes Human Rights Watch.

“Israeli forces began an intense aerial bombardment and later a ground incursion,” which continues as the blog is being written.

“More than 37,900 Palestinians, most of them civilians, were killed between October 7 (2023) and July 1, according to the Ministry of Health in Gaza.

The Palestinian death toll for the first 10 months of the conflict is about the population of the city of San Gabriel in California.

“Israeli forces have reduced large parts of Gaza to rubble and left the vast majority of Gaza’s population displaced and in harm’s way.”

Vigils & Protests Ensue

Harvard’s Kennedy School tracked 470 public events in the US in the ten days following the first attack: 270 in support of Israel and 200 pro-Palestinian.

Using a conservative counting method, crowd sizes topped 180,000 during the period.

Reactions to such events led Dr. Haaken and her team to interview a host of scholars, teachers and students.

For example, the film’s trailer features comments from Premilla Nadasen, a professor of history at Columbia University’s Barnard College.

“What we’ve seen in the past couple of months is a whole series of strategies universities have deployed to censor student and faculty speech in an attempt to curtail academic freedom,” Dr. Nadasen notes.

Columbia was among the first campuses spotlighted for its protests and for the ensuing administrative responses, including arrests by protestors, and charges of “no-confidence” for Columbia’s president by faculty members.

In April, six months after Hamas’ attacks, about 100 students were arrested in pro-Palestinian protests, and Columbia’s president, Nemat (Minouche) Shafik, was skewered by the press and called to answer questions before the US Congress.

In hindsight, it seems Dr. Shafik was ill-prepared for the barrage of insults from multiple sides: students, faculty, Jewish organizations, Palestinian communities, right-wing press, left-wing press, and even members of Congress.

Columbia’s president had served for a little over a year before she resigned last month (16 August 2024), just before fall classes began.

Photographer Tyrone Turner captures protestors taking a break for evening prayer during their demonstrations at George Washington University in the spring. Source: NPR (National Public Radio), 27 April 2024.

The Palestinian Exception

Dr. Shafik’s brief tenure illuminates the tensions surrounding censorship and the discourse of what has been called The Palestinian Exception—the name of Dr. Haaken’s documentary and the nomenclature used when writers command a stance that analyzes Israeli actions critically.

That is: condemnation against Israel is reframed as antisemitic, thus shutting down the critic.

Palestinian exceptionalism harkens back to comments made a decade ago by the late Michael Ratner, a civil rights attorney and activist, who critiqued cultural norms providing that the interpretation of American free speech fails to encompass criticisms of Israel, thus creating “The Palestinian Exception to Free Speech” or to the First Amendment.

The gauntlet has been gripped by many who argue that freedoms encompassing speech, teaching and research should never pivot on what politicians decide as normative.

The most trenchant example of such exceptionalism is seen in the grilling by Representative Elise Stefanik (R, New York) of presidents from Harvard, MIT and the University of Pennsylvania at Congressional hearings in December 2023.

Stefanik accused the trio—all women—for failing to label campus protests as antisemitic.

More than one critic has compared The Palestinian Exception with Senator Joe McCarthy’s persecution of Americans in the wake of the Red Scare’s fear-mongering of communism in the 1950s.

“McCarthy rose to national prominence by initiating a probe to ferret out communists holding prominent positions. During his investigations, safeguards promised by the Constitution were trampled,” according to the US History.org website.

Like McCarthy, Stefanik took credit for upending careers of elites: the three presidents resigned their posts after Stefanik lobbied dishonest, trumped-up claims to disparage the three women who held some of the Country’s most powerful positions as academic leaders.

Currently Stefanik has set her sights on the most powerful woman in New York—Governor Kathy Hochul—armed with a script from Joe McCarthy.

According to her website, Stefanik asked for an investigation a few days ago that accuses Houchel of hiring an aide who the Congresswoman calls a communist.

Fear of communism was tangible during McCarthy’s reign, which was characterized by “hysteria,” according to editors of the website History.com.

“The advances of communism around the world convinced many US citizens that there was a real danger of ‘Reds’ taking over their own country. Figures such as McCarthy…fanned the flames of fear by wildly exaggerating that possibility.”

According to the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union), “thousands lost their jobs, were imprisoned, faced organized mob violence or were forced to leave the country” during the Red Scare.

Faculty and Journalists Fired

As in McCarthy’s era, faculty and media experts have found themselves jobless today for their stance on justice and freedoms resulting in discourse over the war in Palestine and Israel.

- Mohamed Abdou, a visiting professor in Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African studies at Columbia University, will not have his contract renewed in 2024. Intercept columnist Natasha Lennard says a Facebook post from October “was taken wildly out of context” and “has been weaponized to undo Dr. Abdou’s career, after 20 years of teaching in Canada, Egypt, and the U.S. in fields including queer studies and Indigenous studies.”

- A scholar of Japanese literature at the City University of New York’s Hunter College, Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, said a student reported her pro-Palestine social media posts to the head of her department. “Nothing in the posts…was antisemitic,” Dr. Hofmann-Kuroda told Lennard. “The only thing I have done,” she said, “is to criticize the state of Israel for its 75-year brutal occupation of Palestine and criticize Americans for their complicity or silence in this genocide.”

Journalists have also lost jobs for their stance on Israel and Palestine.

- Long-tenured cartoonist for The Guardian newspaper, Steve Bell, was told his contract would not be renewed after he complained on social media about the paper’s “decision not to run an illustration in which he depicted Netanyahu cutting a square of his stomach out with a scalpel in the shape of Gaza,” says Newsweek.

- The editor-in-chief of Artforum magazine—David Velasco—was fired after the magazine published an open letter signed by 8,000 individuals who condemned violence in the war. Velasco told The Guardian‘s Gloria Oladipo, that he has “no regrets. I’m disappointed that a magazine that has always stood for freedom of speech and the voices of artists has bent to outside pressure,” he said.

How to Support the Documentary

You can make a donation of any amount—tax-deductible—at Film Independent.

I care deeply about academic freedom and free speech, and I support the documentary with all my heart (and with my checkbook, too).

You can watch read more about the film at the documentary’s website.

###

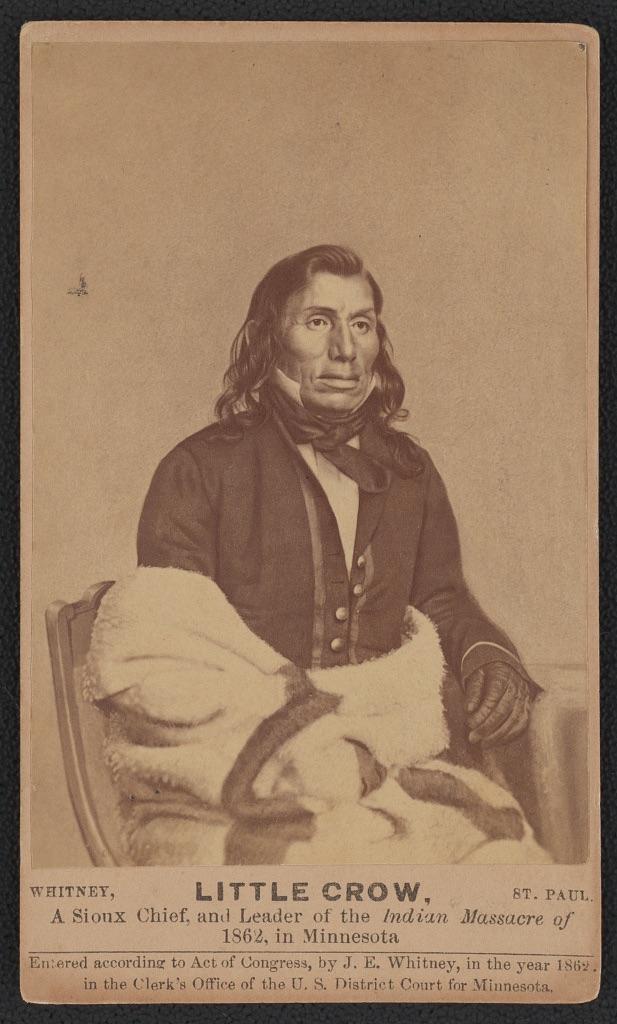

Next up: The connections between The Palestine Exception and freedoms of Native Americans.

I acknowledge the Native peoples on whose land I live, write, and teach, including the Multnomah, the Clackamas, and other Indigenous communities in my region of the Pacific Northwest.

Our city has been threatened by the felon-in-charge (Trump was found guilty on 34 unlawful acts) who declared Portland “war-ravaged,” according to today’s New York Times.

Our city has been threatened by the felon-in-charge (Trump was found guilty on 34 unlawful acts) who declared Portland “war-ravaged,” according to today’s New York Times.